Conservation Across Borders

Forest Reforestation in and near the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve

Monarchs have, for the most part, made their way to their wintering grounds in the mountains of central Mexico or coastal California. Many of us living in monarch breeding and migrating grounds work to conserve and restore the plants that these incredible insects need during the months that they’re here. The same is true of our colleagues near the wintering sites, but instead of protecting and restoring grasslands rich in milkweed and nectar plants, overwintering habitat conservation involves forest protection and restoration.

Most monarchs from the Eastern Migratory Population spend the winter in Mexico, in approximately 56,000 ha (or about 139,000 acres) of protected area called the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve (MBBR). There, in the States of Michoacán and Mexico, the quality of the forests that shelter monarchs is important to their survival from November through mid-March, when they are neither migrating nor breeding.

Alternare A.C., a Mexican non-profit organization, has worked for over 22 years to support conservation in monarchs’ wintering sites in central Mexico. Alternare staff work closely with the rural communities and ejidos in the region. Their work centers on training and supporting these communities – with joint goals of improving their quality of life and environmental conservation. Through many partners and funders, including the US-based Monarch Butterfly Fund, Alternare carries out reforestation in degraded areas in and near the MBBR, where land use change for agricultural purposes, illegal logging, and overgrazing leads to the degradation of forest ecosystems.

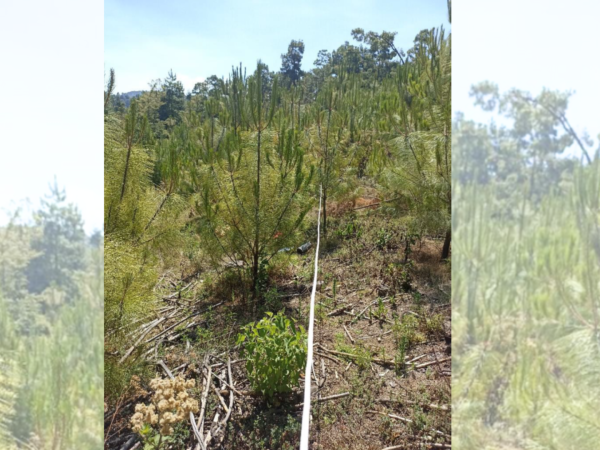

Since 2010, Alternare has reforested more than 300 hectares in the MBBR and surrounding areas. Reforestation begins with the production of plants in community nurseries and schools, where community members are trained in production and reforestation practices. These trees become part of intact forests that will support monarchs, and in some cases provide environmentally friendly sources of income for these communities, for whom forestry products are an important source of income. All trees are native to the region and are grown from seed sourced in the local area; they include smooth-bark Mexican pine (Pinus pseudostrobus, known in Spanish as chamite or pacingo), Oak (Quercus sp.), Ash (Fraxinus sp.), Oyamel (Abies religiosa) and alder (Alnus acuminata).

An Alternare team assesses these reforestation efforts by surveying planted sites. Surveys conducted in 2015, 2018 and 2019 assessed plantings carried out before 2019. In 2023, they surveyed sites that had been planted in 2019-2021 in collaboration with Indigenous Communities (Crescencio Morales, Francisco Serrato and El Asoleadero), and ejidos (San Juan Zitácuaro and Manzanillos). They selected 23 out of a total of 67 reforested sites to sample – in total Alternare teams planted 66,660 trees in 66 hectares of land from 2019 to 2021. In addition to tree survival, they measured the height of living trees and assessed factors that might have affected survival, like grazing activity, fencing, and care by the local community.

On average, 68% of the planted trees had survived, a result that is considered good by reforestation specialists. However, at individual sites, survival ranged from 0% to 100%. In general, sites that were planted by communities who are committed to the land because they can use it, that are far from populated areas, and where grazing is not permitted had higher survival. Sites with low survival had often undergone a change in land use; trees had been displaced by crops such as corn, avocados, and peaches. One low survival site had high rates of grazing and thus trampling, and another close to an urban area was full of debris and evidence of garbage burning.

In addition to factors that affected post-planting success, Alternare has learned that sites and planting protocols with specific characteristics affect success. Sites with less than 30% canopy coverage and fewer herbaceous plants to compete with the newly-planted trees tend to have higher success. In some cases, this means that site cleaning (chaponeo) is called for. In addition, sites that were forested in the past are more likely to have high survival. The quality of trees being planted is important too; trees that are produced close to the reforestation sites are less stressed because they don’t need to be transported as far, and trees planted in the morning when the temperature is lower are more likely to survive. Alternare staff provide help to the communities before reforestation work begins, including advice on how trees should be handled as they are extracted by the bags or trays used for transport and how closely together they should be planted.

Because conservation almost always involves decisions about how to allocate scarce resources, Alternare’s surveys and their use of what they learn is a wonderful example of informed and successful conservation.

Dr. Karen Oberhauser