Article by Dr. Karen Oberhauser: Monarch Winter 2022–2023 Population Numbers

Monarch Winter 2022–2023 Population Numbers Released

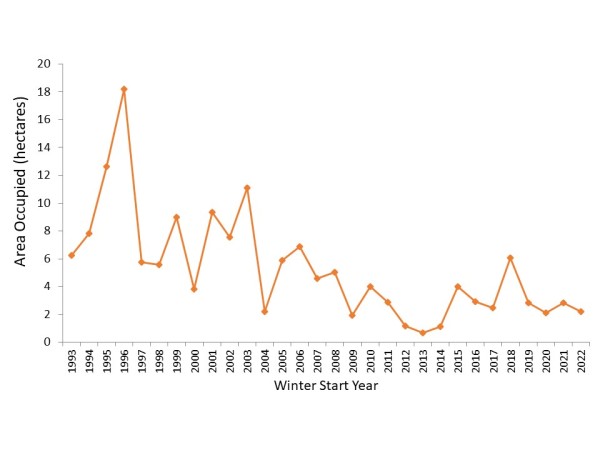

On March 21, 2023, the World Wildlife Fund-Telmex Telcel Foundation Alliance (WWF) and the National Commission of Protected Natural Areas in Mexico (CONANP), released data from the winter 2022–23 monarch butterfly population counts. At the wintering sites in central Mexico, monarch population size is compared from year to year by the number of hectares (one hectare = 2.5 acres) occupied by trees containing monarchs. WWF and CONANP have been monitoring this area since 2004, with similar data from 1993-2003 collected by the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve (MBBR). While the number of monarchs in a hectare varies from year to year and is difficult to estimate, our best estimate is that the average is about 21 million.

In December 2022, monarchs occupied 2.21 hectares, compared to 2.84 hectares at the same time in 2021, or a 22 percent decrease. The average for the past decade is 2.75 hectares, and the population has been declining since we began measuring it (see graph).

The amount of summer breeding habitat available for monarchs sets an upper limit, or ceiling, for how many monarchs travel to Mexico at the end of summer. The number of migrating monarchs varies, up to that value, depending on weather conditions. We probably got close to the ceiling in summer 2018, leading to the largest winter colonies in over a decade. Weather conditions that spring, summer, and fall were good for monarchs.

Before the advent of genetically modified herbicide-tolerant crops, corn and soybean fields contained a lot of milkweed, monarchs’ larval host plant. From about 1999 through 2007, the amount of breeding habitat was drastically reduced by increased use of herbicide-tolerant crops and subsequent loss of milkweed in corn and soybean fields. Monarchs used milkweeds in corn and soybean fields extensively for egg laying, and their loss is reflected in a drop in monarch numbers over this period.

After about 2010, almost all corn and soybean fields contained herbicide-tolerant crops. Since then, habitat availability hasn’t changed a lot, and the winter monarch population fluctuates around an average just under 3 hectares – it is higher when weather conditions are ideal for monarchs, and lower when they’re not very good. The lower numbers in winter 2022-2023 reflect what we observed in the northern breeding grounds last summer.

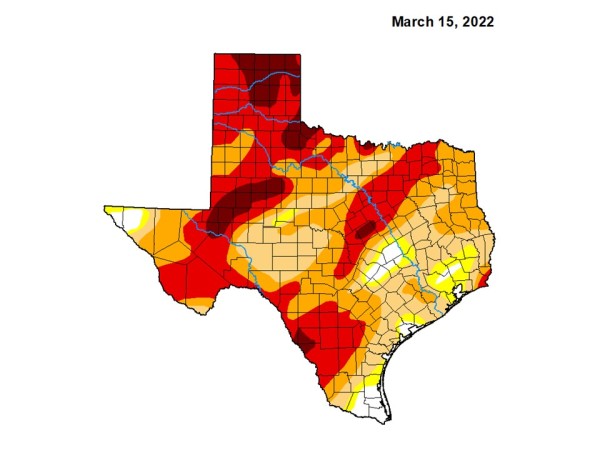

A 2021 analysis* shows that the most important factor affecting winter numbers is summer population size. Summer population size is driven by several factors, but the important is weather in the southern United States in the spring--when monarchs are migrating north from wintering in Mexico. Summer weather, overall herbicide use in crop fields, and late winter population size are also contributing factors. Hotter, drier, colder, or wetter conditions in the southern U.S. are bad when monarchs are moving through. Last spring was very dry – see the drought monitor map from a year ago. One effect of climate change is more extreme weather variability, which may pose additional challenges to monarchs.

The best way to support monarchs is to raise the ceiling by creating more habitat. That means an all-hands-on-deck approach: restoring habitat in our yards, places of work, schools, and churches; along roadsides, utility rights-of-ways, and railroads; and in areas currently used for crops that aren’t very productive. This work supports monarchs and thousands of other species in the same habitats.

We also need to work to mitigate climate change. This week's report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change needs to be a call to action; we know that the conditions predicted by climate models will be bad for monarchs, but they’ll also be bad for us and most other organisms on earth.

*Zylsta, ER, Ries, L, Neupane, N., Saunders, SP, Ramirez, MI, Rendon-Salinas, E., Oberhauser, KS, Farr, MT, Zipkin EF. 2021. Changes in climate drive monarch butterfly dynamics. Nature Ecology and Evolution. 5:1441–1452. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-021-01504-1

--Karen Oberhauser, UW-Madison Arboretum