Each fall, monarchs from across North America that emerge around mid-to-late August and beyond will take on a trip of potentially 2,000 miles or more, making their way over forests, farmland, prairies, and even lakes on their way to overwintering sites, primarily in Mexico and California.

While many butterfly species overwinter as adults or as pupae, the monarch undertakes one of the world's most incredible migrations, reaching places they've never been before and coming together in potentially massive clusters.

The eastern migration

Decreasing day length and temperatures, along with aging milkweed and fewer nectar sources, trigger a change in monarchs; this change signifies the beginning of the migratory generation. Unlike summer generations that live for two to six weeks as adults, adults in the migratory generation can live for up to nine months. Most monarch butterflies that emerge after about mid-August in the eastern U.S. enter reproductive diapause (do not reproduce) and begin to migrate south in search of the overwintering grounds.

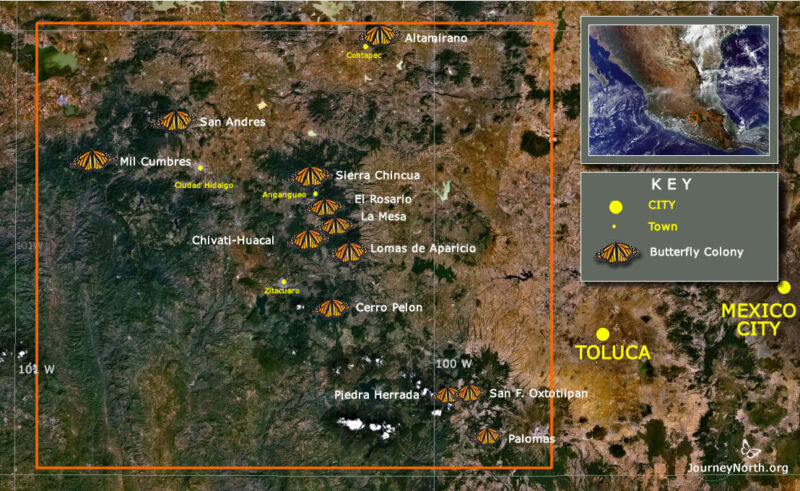

From across the eastern U.S. and southern Canada, monarchs funnel toward Mexico, where they take refuge in oyamel fir trees on south-southwest-facing mountain slopes. These locations provide cool temperatures, water, and adequate shelter to protect them from predators and allow them to conserve enough energy to survive winter.

How are monarchs counted?

Monarchs in Mexico congregate in clusters by the millions. Because there are so many monarchs so highly concentrated, scientists measure them by the area they occupy.

Scientists walk the forest and decide which trees have enough butterflies to be considered part of the colony, marking the edge.

The area is measured in hectares (about 2.47 acres). The number of monarchs will vary per hectare, but it's estimated to be between 20 and 30 million per hectare (median 21.1, according to Thogmartin et al., 2017).

Monarchs, mountains, and moisture

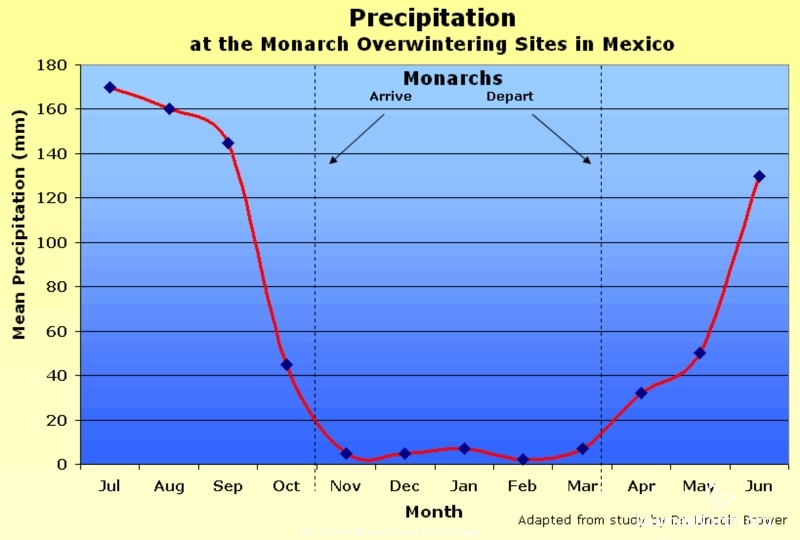

Moisture is crucial for monarchs' overwintering success in Mexico. The late Dr. Lincoln Brower hypothesized that one of the reasons monarchs overwinter where they do is because the high-altitude mountains of the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve capture moisture.

The high-altitude mountains capture moisture through a process called adiabatic condensation. As moisture-laden air rises, it expands and cools, and clouds form. At high altitudes, the moisture condenses as water droplets on the needles of oyamel fir and pine trees.

On the morning of Dec. 11, 2006, Brower took the photo below, which shows condensed mist frozen on the open area of Cerro Pelon, known as the Llanos de los Tres Goberonores. In the second image, you can see monarchs -- Brower estimated there were several thousand -- drinking dew after the sun's rays warmed the frosted ground and melted the frost into dew.

Mexico's dry season begins as monarchs arrive in November and lasts until they leave in March. The air becomes increasingly scarce as the months go by, drying out the forest and the butterflies. Even dew becomes scarce.

By March, the monarch's winter habitat is quite dry. The colonies break up as butterflies fly out in search of water. They move down the mountain into the lower portions of the watersheds. It's important that the entire watershed is protected so monarchs can find moisture in these crucial final weeks before spring migration.

The western population

Fourth-generation western monarchs require nectar to build lipid reserves as they migrate south and west to the overwintering sites along the California coast (also in Baja California and Arizona), arriving around late October.

Once they arrive, they roost for the winter in eucalyptus, Monterey cypress, Monterey pine, and other trees, sometimes in aggregations of thousands of individuals. In February and March, reproductive diapause ends and the annual cycle starts anew.

As of 2025, numbers have dropped at overwintering sites in California. In 1997, over 1 million monarchs were counted at about 100 sites. In 2024, numbers dipped to below 10,000. Learn more from the Western Monarch Count, organized by The Xerces Society. You can view a map of overwintering sites here.

In areas of the desert southwest, monarchs use nectar and milkweed plants throughout much of the year.